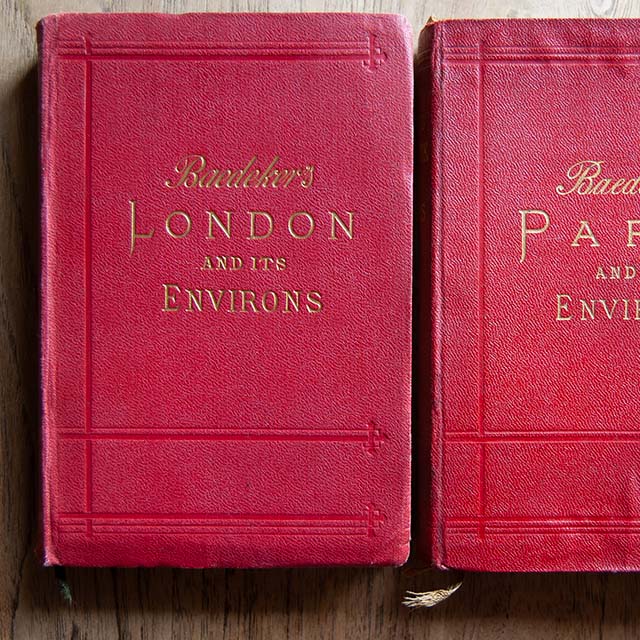

Published by German book publisher Karl Baedeker, the first Baedeker guide for travelers — Die Schweiz: Handbuch für Reisende, nach eigener Anschauung und den besten Hülfsquellen bearbeitet — came out in the mid 1800s, and the first English issue of a Baedeker guide came out in the 1860s. Baedeker wasn’t the first or the only travel guide on the market, but they were so successful that Baedeker entered the English vocabulary as a noun simply meaning “a guidebook to countries or a country.” Supposedly, one could even go baedekering which meant to travel around in order to either write a guide or to write some sort of travel story (although, maybe don’t quote me on that one: my sources for this dictionarial claim are a little short on their references).

The Baedeker guides were for times when you needed help distinguishing between those trains “which start somewhere and get nowhere and those which start nowhere and get somewhere,” minutiae and larger facts assembled and carefully edited by somebody who was — as James Muirhead put it — “at once scholar and sportsman, bon-vivant and botanist, archaeologist, and theatre-goer.”

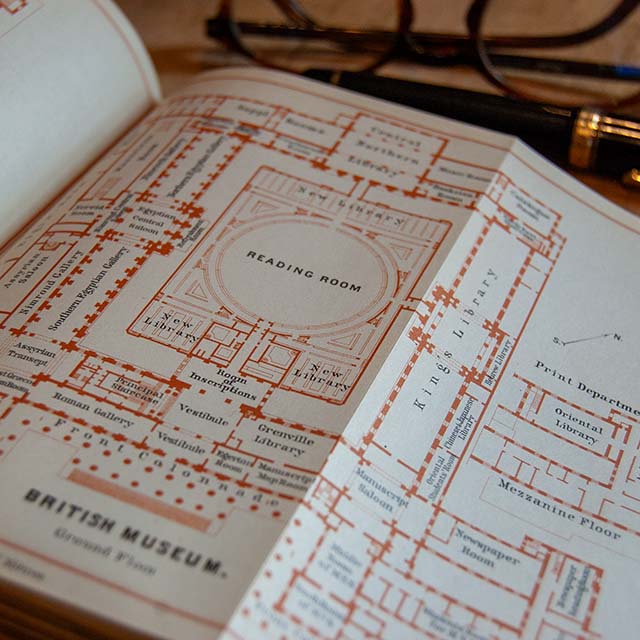

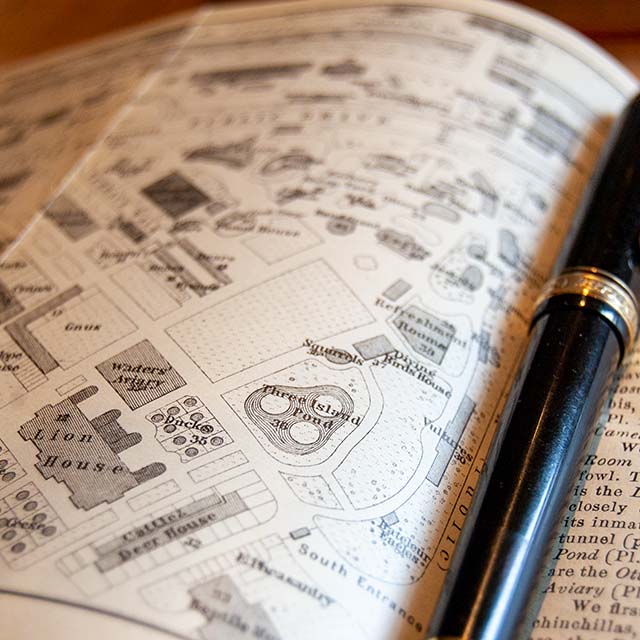

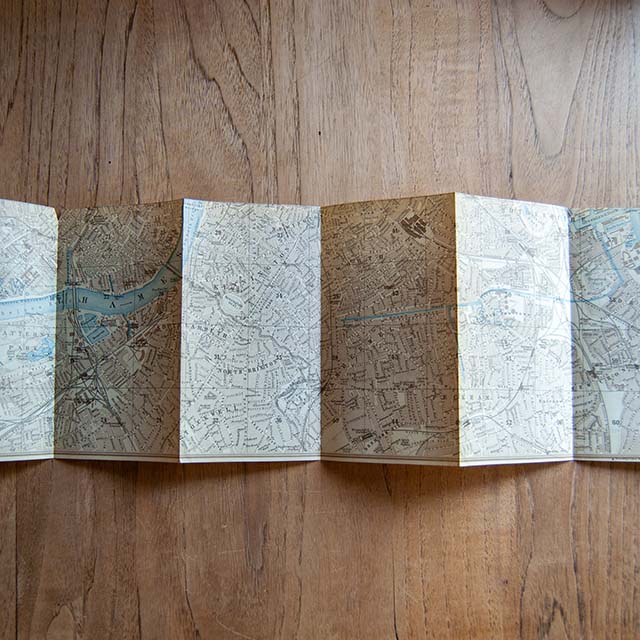

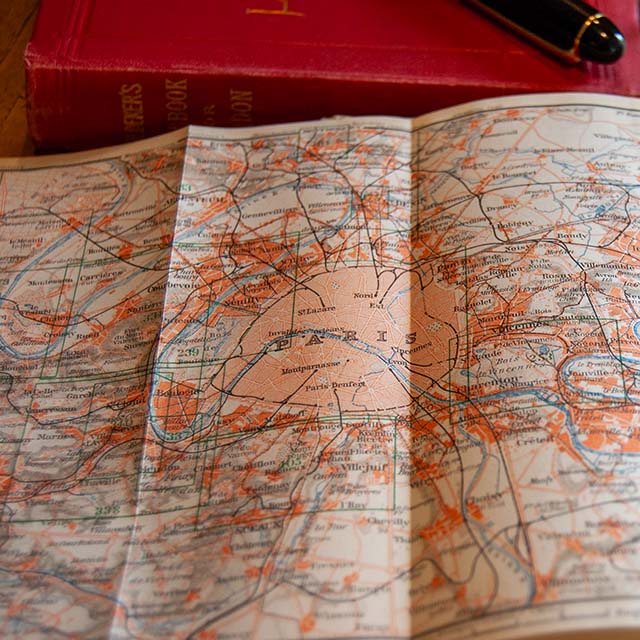

In my 1908 edition of London and its Environs, 30 pages are dedicated to the British Museum, and in the 1924 edition of Paris and its Environs, 85 pages concerns the treasures of the Louvre. My 2010 Lonely Planet on London has 1 page about the British Museum, and my Paris guide from 2011 has 1 1/2 page on the Louvre: 100-ish years have past since the publications of the Baedekers, and in that time travel guide books have changed.

The hat is usually raised to ladies only, and is worn in public places, such as shops, cafés, music-halls, and museums. It should, however, be removed in the presence of ladies in a hotel-lift (elevator).

Baedeker Raids:

One of Karl Baedeker’s innovations was to assign asterisks in the text, next to some establishments or sites, “as sign of commendation.” During WWII this led to denominating certain German air raids on England as the Baedeker Raids, where — in order to demoralize the English population — the German Luftwaffe chose bomb targets for their cultural and historical significance. The campaign has been called the Baedeker Raids because one German propagandist reportedly declared that their tactic was to “bomb every building in Britain marked with three stars in the Baedeker Guide.” My 1908 edition of the London guide seems to only use one and two asterisks, so perhaps later editions added a third for those especially commendated sites. Photo: Martin Høyem

Bibliography

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. 5th edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

- Baedeker, Karl. London and its Environs: Handbook for Travellers. Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1908.

- ———. Paris and its Environs with Routes from London to Paris: Handbook for Travellers. Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1924.

- Cave, Roderick, and Sara Ayad. The History of the Book in 100 books. New York: Firefly Books, 2014.

- Muirhead, James F. “Baedeker in the Making.” The Atlantic Monthly May 1906.