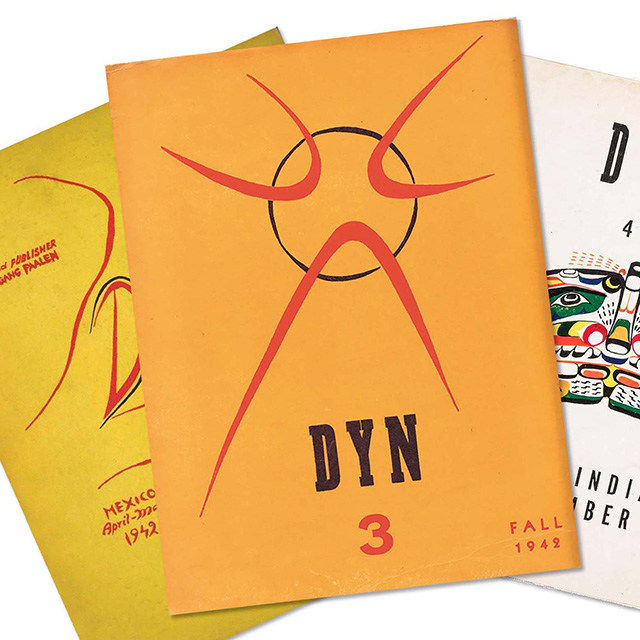

In 1942, Austrian-born artist Wolfgang Paalen (1905-1959) launched Dyn magazine from his base in Coyoacán in Mexico. In an article featured in the first issue, Paalen — who had been a member of the surrealist movement in Paris before WWII — declared his “Farewell au Surrealisme.” Supposedly this caused big controversy in the art world. “His secession,” writes Dawn Ades “sent a shock wave through the American surrealist groups ...” (Farewell to Surrealism: The Dyn circle in Mexico).

Paalen’s main beef with the Surrealists was their insistence on Marxist Dialectics: In “The Dialectical Gospel” — an essay published in the second issue of Dyn — Paalen expands on his critique: “The dead weight of Dialectic Marxism constitutes an obstacle to a truly revolutionary fusion with modern science, art, and philosophy.”

(p. 54). The “controversy” of Paalen’s farewell, was to call out dogmatic discourse as unfruitful. And for the dogmatic — left as well as right — this standpoint is, of course, unacceptable.

I admit that I struggle to fully grasp the essence of the controversy and the apparent deepfelt emotions behind the dispute. But that is probably because the full consequence of Surrealist political discourse is somewhat lost on me. It can be hard for us, people of the future, to understand the alarming reality of 1930’s Europe and the underlaying traumatic pulse — we can’t fully comprehend how it felt to live in those uncertain, violent times and not know what would happen next. When we think of Surrealism, we think quite simply of a melting clock, an elephant with very long legs, or perhaps a man in a bowler hat with an apple floating in the air in front of his face; we tend to leave out the context of fascism and Hitler and Stalin and civil war and genocides, and what may come, because those are not apparent in the art. But the hard reality of that context, and the discourse around it, was of absolute urgency to the Surrealists.

Ideological trench war is ubiquitous, familiar even to people who don’t engage in battles. The intellectual face-offs perpetually flow and ebb the cultural landscape, past and present, always threatening to flame up into real physical — perhaps even violent — action.

My indifference to the supposed controversy might have pleased the creators of Dyn. While I’m not myself a stranger to a little bit of dogmatism, I find it refreshing to move around in a landscape which, rather than being a battleground for ideological theorizing, concerns itself with stimulating philosophical and aesthetic curiosity.

The name Dyn is derived from the Greek κατὰ τὸ δυνατόν (pronounced katá tó dynatón) — meaning “that which is possible.” The magazine existed only for a short time — six issues were published between 1942 and 1944.

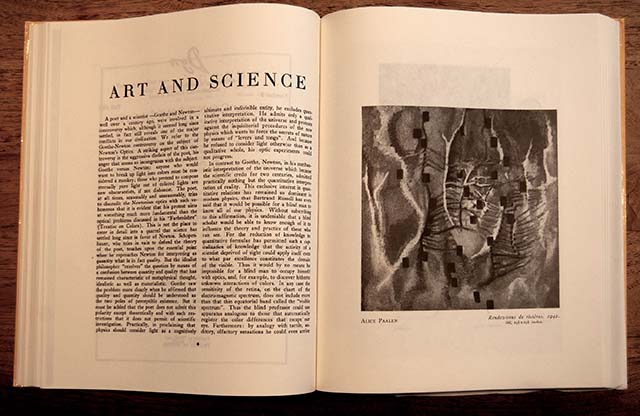

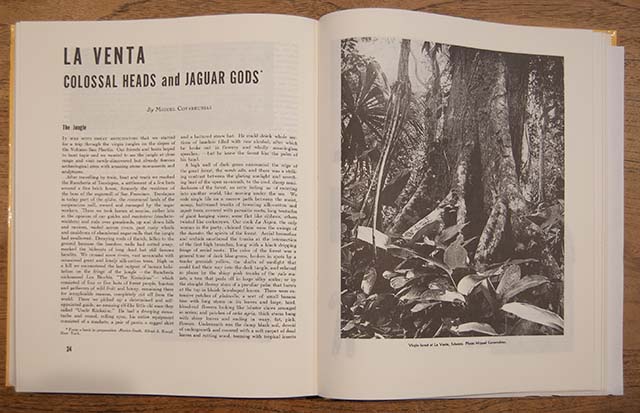

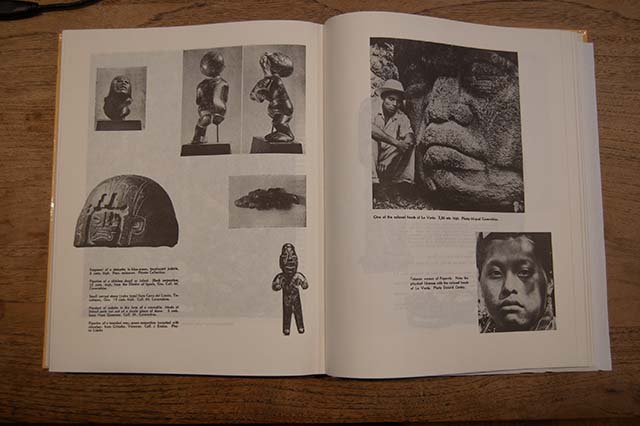

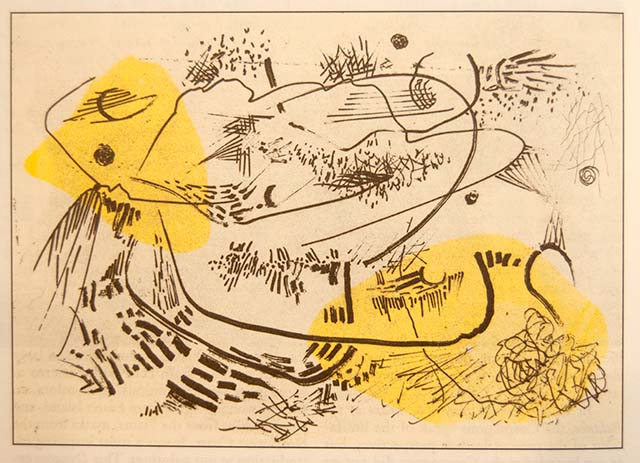

Whenever art history, aesthetic studies, and anthropology fraternizes, my interest is piqued. And so, while Paalen’s farewell certainly is of interest to the connoisseur of art history, my favorite articles are Alfonso Caso’s and Miguel Covarrubias’s writing on Mexican archaeology. But there’s a good deal of interesting material here: people like Picasso, Anaïs Nin, Henry Miller, Alice Paalen (Rahon) and Manuel Álvarez Bravo also contributed with writing and artwork.

Some books about Dyn:

- Ades, Dawn, Donna Conwell, and Annette Leddy. Farewell to Surrealism: The Dyn Circle in Mexico. Los Angeles, California: Getty Research Institute, 2012.

- Paalen, Wolfgang, and Christian Kloyber. Wolfgang Paalen's Dyn: The Complete Reprint. Wien: Springer, 2000.