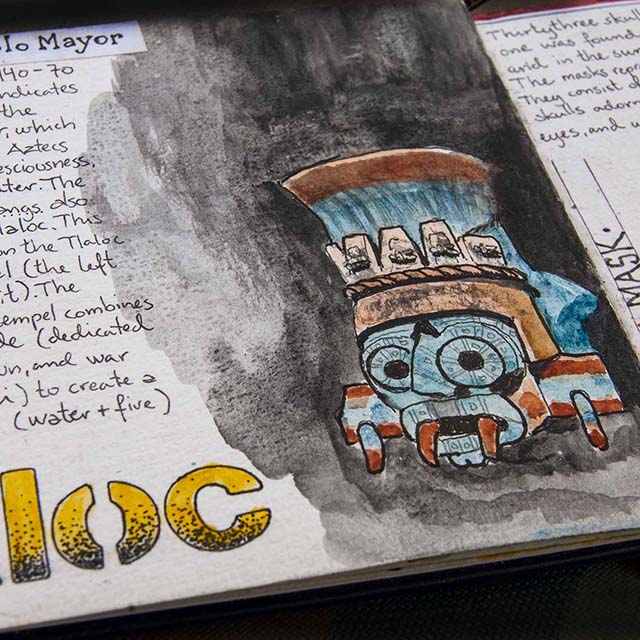

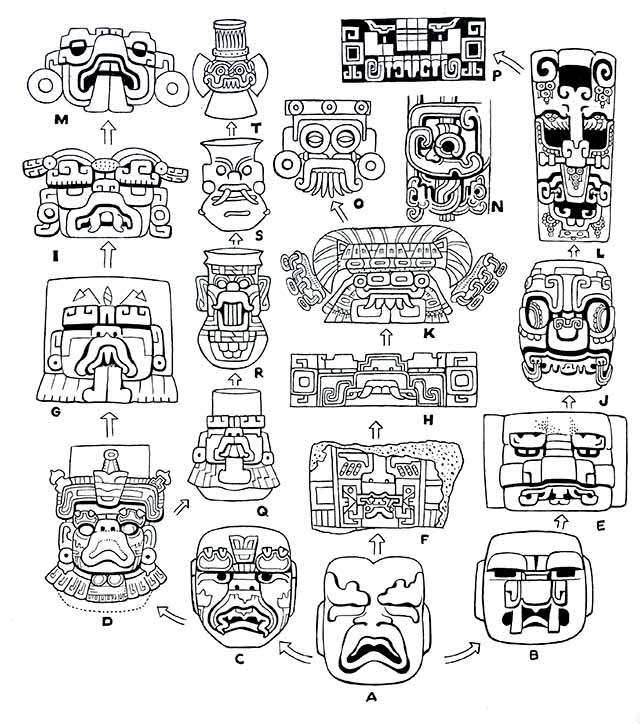

Alfonso Caso (1896-1970), Mexican archaeologist extraordinaire and excavator of tomb 7 at Monte Albán, points it out in The Aztecs, People of the sun: the Aztecs were mostly agricultural and thus the rainy season and other atmospheric phenomena that influenced sowing and growing and reaping was of great consequence to them. Therefore it is no surprise to learn that Tlāloc, the God of rains and lightning — “he who makes things grow” — was one of the most important gods to the Aztecs. And not only to the Aztecs: the Mayas (who called him Chaac), the Totonacs (who called him Tajín), the Mixtec (who called him Dzahui), the Purépecha (who called him Chupithripeme), the Zapotec (who called him Cocijo), and the Olmecs, too, they all worshipped the same god.

“He is […] probably the most ancient of the gods worshipped by man in Mexico and Central America,” writes Caso.

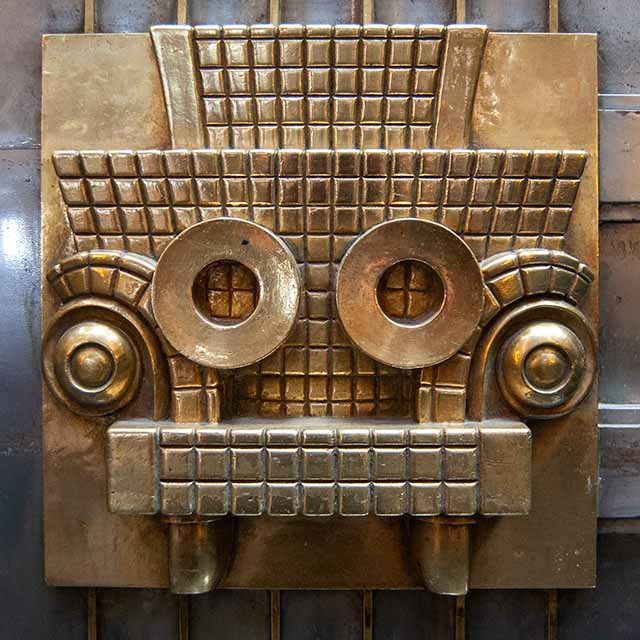

Tlāloc is the most depicted god at Teotihuacan, and one of Tenochtitlan’s two temples of the Templo Mayor was dedicated to him.

The name Tláloc derives from the Nahuatl words tlali which means ‘earth’ and oc which means ‘something on the surface.’ (I have also seen it etymologically referred to as ‘path beneath the earth’ which — in light of the previous explanation — seems curious, but which I am drawn to because I like hidden paths.)

Bibliography

- Berrin, Kathleen and Virginia M. Fields. Olmec: Colossal Masterworks of Ancient Mexico. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

- Caso, Alfonso. The Aztecs: People of the Sun. Tranlated by Lowell Dunham. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1958.

- Covarrubias, Miguel. Indian Art of Mexico and Central America. New York: Knopf, 1957.

- Miller, Mary E, and Karl Taube. An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1993.

- Robb, Matthew H (ed.). Teotihuacan: City of Water, City of Fire. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and University of California Press, 2018.