One of the earliest Mesoamerican cities, Monte Albán was established by the Zapotecs and was their center of power as they ruled the surrounding valleys for nearly a thousand years. It’s situated nine kilometers southwest of Oaxaca de Juárez in the Mexican state of Oaxaca. By AD 900–1000 the city was largely abandoned, but was occasionally used by the Mixtec. Extensive archaeological fieldwork started in 1931, under the guidance of Mexican archaeologist Alfonso Caso.

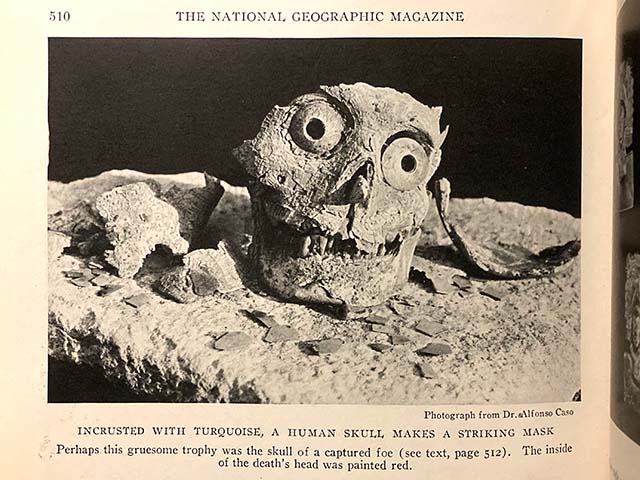

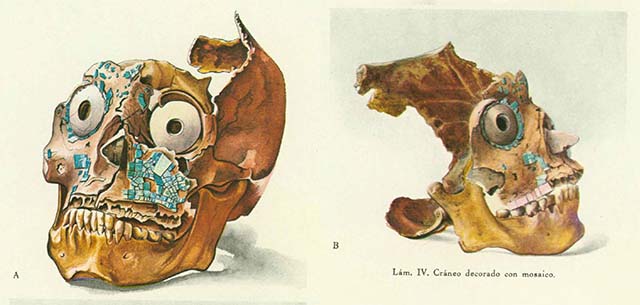

This skull was found in tomb 7 in Monte Albán. In the October 1932 issue of National Geographic Magazine, Caso describes the skull like this:

The only mosaic that was preserved, although much damaged, is one made of a human skull (…), probably that of some great warrior captured and sacrificed by the Mixtecs. Afterwards they used it as a macabre war trophy, making an opening in the top and painting it red inside. The turquoise mosaic was then affixed with a paste made principally of copal, a substance anciently used by the Mexicans as incense. An imitation knife made of shell was placed in the hollow of the nose.

The skull has also been described as an incense burner, for example in an article in Current Anthropology written by Sharisse McCafferty and colleagues:

The mosaic skull incense burner found on the altar of amaranth dough in the first chamber relates well to images of skeletonized goddesses that appear in Mixtec codices. Skulls with stone knives are part of the diagnostic costume of the Mixtec goddess 9 Monkey…

At the excavation of Tenochtitlan, many skull-masks were found with sacrificial knives inserted to simulate nose and tongue. These mask or skulls represented the Aztec god of death, Mictlantecuhtli.

Now, of course Aztec and Mixtec culture aren’t the same. But they partially overlap in time, so it’s easy to imagine elements of major cultural diffusion as a result of exchange and trade, and that the significance of the shell that represents the nose in this Mixtec skull from tomb 7, could be similar to what the sacrificial knives signified for the Aztecs when they used them as noses in the Templo Mayor skulls.

For a long time archaeologist theorized that turquoise found in Mexican archaeological sites originated from the territories that are now the US Southwest and the northernmost parts of Mexico, and ended up in central and southern parts of Mexico as a result of long distance trade. In the National Geographic article Caso mentions this idea, but opines that “the wealth of turquoise in Tomb 7 and the fact that in the Aztec tribute books various towns in the regions of Oaxaca and Guerrero contributed turquoise demonstrate […] that there must exist in these States old mines of turquoise which a systematic investigation may uncover.

”

In 2018 a group of scientists strengthened this theory: they looked at isotopic signatures of some samples of turquoise from Tenochtitlan (in other words from Aztec culture) and some others from Mixtec areas in present day state of Puebla, and concluded that the stones do not originate from the Southwest, but rather must come from hitherto unknown mines in Mesoamerica.

Bibliography

- Alyson M. Thibodeau et al. “Was Aztec and Mixtec turquoise mined in the American Southwest?” Science Advances 4(6), 2018.

- Caso, Alfonso. El tesoro de Monte Albán / Estudios técnicos sobre la Tumba 7 de Monte Albán. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia: Mexico D.F., 1969.

- ———. “Monte Albán, Richest Archeological Find in America” The National Geographic Magazine, 62:4, 1932.

- McCafferty, Sharisse D., et al. “Engendering Tomb 7 at Monte Alban: Respinning an Old Yarn [and Comments and Reply].” Current Anthropology, vol. 35, no. 2, 1994, pp. 143-66.